<

strong>KABUL / KUALA LUMPUR, March 25 (Bernama) – When news broke that the Taliban was back in charge of Afghanistan for the second time since their ouster in 2001, education activist Sameera Noori could not stop crying.

As a woman, she thought life as she knew it was effectively over. As an educator, she saw her hopes and dreams of helping Afghanistan, especially its girls, develop and succeed evaporate.

“In the past six months, I had to colour my hair. All my hair became grey,” the 29-year-old told Bernama in her office in Kabul. “Even now, I’m quite depressed. I lost interest in everything. I had my plans, I had my goals … I would do this and that, I would publish a book. Now, I am not much interested in anything.”

The latest development in girls’ education has not reduced her stress levels. High schools for girls, which have been closed since August 2021, were supposed to reopen three days ago on Wednesday. The spokesman of the Afghan Ministry of Education even made a video congratulating everyone on their return to school the day before.

Reopening high schools for girls would fulfil one of the promises the Taliban made to the international community, including Malaysia.

Instead, the leadership backtracked on their promise a few hours after the schools (teaching Grades 7 to 12) reopened and announced that they will remain closed till further notice, prompting confusion from some and condemnation from others. However, high schools in Herat and Badghis provinces remain open for all girls to date.

Social media was full of videos of sobbing teenage schoolgirls wanting to go to school.

The government initially did not give a reason but later said they had concerns over the school uniforms to ensure they are in accordance with Islamic law and Afghan culture, which many saw as a deflection.

Sameera Noori, Ketua Pendidikan bagi Citizen’s Organisation for Advocacy and Resilience. --fotoBERNAMA (2022) HAK CIPTA TERPELIHARA/ Nina Muslim

While a few have tried to argue that this was just a teething problem for a regime unused to governing, Sameera was vexed with what she saw as another sign of the regime’s unreliability.

“(I) really don’t know what they want and why they are doing (all this),” she said via WhatsApp.

This latest reversal, taking place about a week before a donor conference, is another setback in the new regime’s pattern of possible backsliding into the Taliban’s previous rule, when girls were banned from going to school. Since taking over after the US withdrawal and the fall of the US-backed Ashraf Ghani government, the Taliban has been desperate for recognition from the international community, which would end the economic and banking crisis currently happening in Afghanistan.

One of the conditions of recognition and international aid funding is girls’ education.

TRADITIONAL BELIEFS

Seorang bapa memujuk anak perempuannya apabila Taliban menutup semula sekolah menengah perempuan beberapa jam selepas dibuka di Afghanistan. Twitter @AbdulHaqOmeri

Activists and journalists in Afghanistan have posited the last-minute cancellation was due to friction between the hardliners, who want to keep to the old ways, and the more moderate factions of the Taliban, who want to open girls’ schools as promised. High schools for boys have been open since September last year. Universities in Afghanistan opened on Feb 26.

The fight is centred around secondary schooling for girls, an issue that seems to have existed for ages.

During the previous Taliban regime, female education was a contentious issue – girls were banned from going to school and university – on top of a ban against most employment opportunities for women. The Taliban promised their rule will be kinder and more moderate this time around, guaranteeing women’s rights in accordance with Islam.

Nevertheless, the Taliban has introduced more restrictions on girls and women in the past few months, such as requiring female students planning to study abroad to travel with a close male relative.

While female education was allowed and encouraged during the US-backed government rule, the aversion to educating girls aged 10 and above runs deep in some parts of the deeply traditional and conservative country. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates at least 60 percent of the 3.7 million children who are currently out of school in Afghanistan are girls.

Sameera, who is the head of education with the Citizens' Organisation for Advocacy and Resilience, said many parents thought educating girls would lead them astray from Islam. She runs the Accelerated Learning Programme (ALP) in Ghazni Province, in southeastern Afghanistan. The ALP targets boys and girls aged above 10 and squeezes four years of instruction into two years.

“When I implemented this project, the people in Ghazni said I’m just trying to teach their children the lessons of the kafir people (non-believers), I’m coming here to teach their children to leave them, to go away,” she said, adding that the families tended to relent after they saw the curriculum, which includes Islamic education.

She also said this mindset was common among families in some provinces and many girls were not able to go to school as a result.

Hasina Sidiqi, anak yatim di Jalalabad, Afghanistan. --fotoBERNAMA (2022) HAK CIPTA TERPELIHARA/ Nina Muslim

One such woman is 28-year-old orphan Hasina Sidiqi in Jalalabad, Nangarhar Province, who never attended school. When asked why, she said her uncle, who was the patriarch of the family, did not believe in educating girls.

“I have to take care of my brothers instead,” she told Bernama through an interpreter. She has two brothers, aged 20 and 23. The older brother is in prison, while the younger one is in university.

While these sociocultural factors and traditional beliefs may have played a part in the closure of girls’ high schools in Afghanistan, there are also other factors in play, including the current economic crisis and the shortage of facilities and teachers.

QUALITY ISSUES

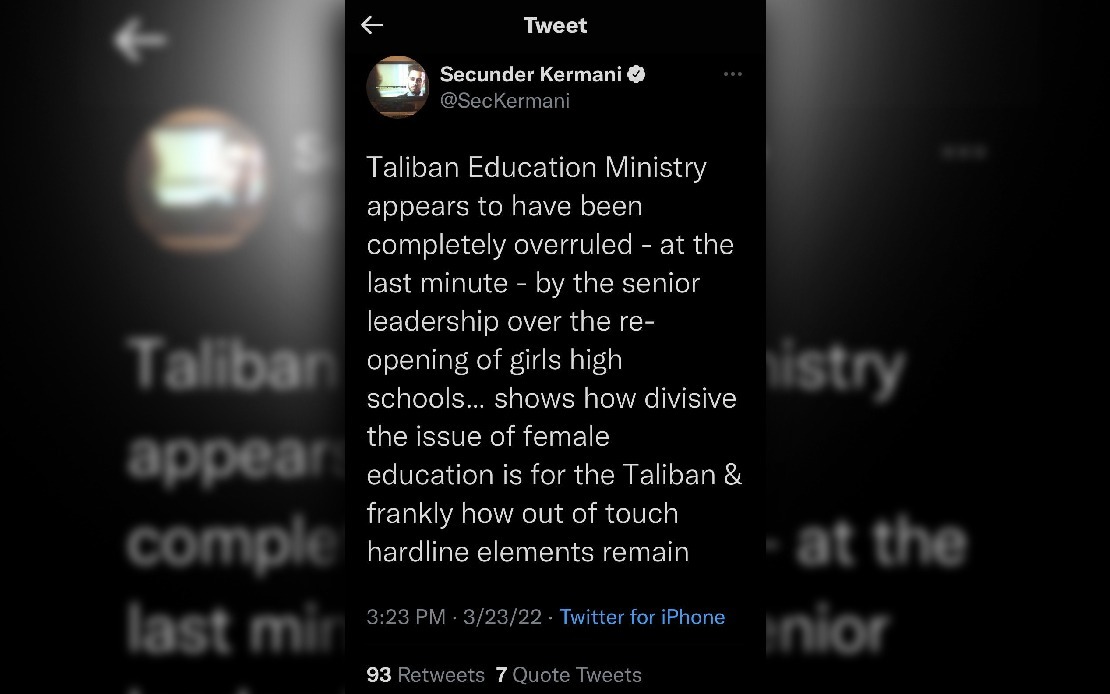

Twitter daripada Koresponden BBC di Afghanistan berkenaan sekolah menengah untuk kanak-kanak perempuan. Twitter@SecKermani

When the Taliban took over last year, many fled Afghanistan fearing the return of the brutality and harshness that marked its previous rule. Among those who left the country were teachers and professors.

On top of that, the fall of the US-backed government to the Taliban triggered sanctions, which led to the freezing of its assets and donor funds earmarked for rebuilding the country.

Although the World Bank recently approved unfreezing some US$1 billion to help finance education, health and family programmes under the UN, the funds will not be enough to cover the salaries of teachers and lecturers, whose numbers are already stretched thin following the Taliban takeover. The new gender segregation rules in schools and universities are also exacerbating the shortage.

Educational activist Obaidallah Faisal was confident the closure of high schools for girls was just a hiccup due to the shortage of female teachers for girls. He said the Taliban will soon have to make a decision to allow male teachers to teach female high school students.

“There is no guideline that says male teachers may not teach (girls). I hope they will allow male teachers to teach because (the government doesn't) have any other way, they don’t have any other means (to make up for the shortage of female teachers),” he said.

Obaidullah, who is the director of Helping Hands for Relief and Development – Afghanistan, added that high schools should follow the example of universities.

In most universities, male lecturers are allowed to teach female students but female lecturers are forbidden from teaching male students. Due to a shortage of professors, Kabul Medical University is currently allowing its female lecturers to teach both classes.

Microbiology professor Dr Abdullah Asady told Bernama the new rules meant the quality of education students get was less than ideal. This is because teachers now have to teach the same class twice, which leaves them with little time to help students.

(Gambar Hiasan) Salah satu syarat pengiktirafan kerajaan Taliban dan bantuan kewangan antarabangsa ialah pendidikan bagi remaja perempuan. Photo: Oliver Weiken/dpa

“In terms of workload, (it has become more difficult). And also, our salaries have been cut down to half,” he said, adding that the current situation was not sustainable.

He is one of the lucky ones. Sameera said most teachers will not get their salaries, adding that the pay cut and non-payment of salaries for teachers were likely a contributing factor to the high schools’ closure.

She said the issue pertaining to the schools was initially considered settled as education activists and aid agencies had already come to an agreement with the Ministry of Education to reopen the girls’ high schools on March 23.

“So again the education cluster and development donors will have to arrange for an emergency meeting,” she said.

CONFUSION AND CONDEMNATION

The sudden reversal in the Taliban’s decision to reopen girls’ high schools has drawn confusion, condemnation and criticism from parents, the UN, diplomats and humanitarian agencies.

Penasihat Khas Wisma Putra di Afghanistan dan Pengerusi Misi Keamanan Global Malaysia Datuk Ahmad Azam Ab Rahman menyerahkan bantuan makanan kepada seorang balu di Kabul, Afghanistan pada 26 Feb 2022. --fotoBERNAMA (2022) HAK CIPTA TERPELIHARA/ Nina Muslim

Even Wisma Putra's Special Advisor on Afghanistan Datuk Ahmad Azam Ab Rahman seemed a bit perplexed by the Taliban's decision to cancel high school for girls. However, he said this did not mean the Taliban government was returning to its old ways.

“In my meeting with the (Afghanistan) Ministry of Education, they seem to be open with various models, including (the) Malaysian model. They need some time to find a suitable model, which is (in accordance) to their understanding and must conform to Islamic principles," he said.

He added the international community should not be so hasty in condemning the Taliban but instead consider the cultural sensitivities in play. He again asked the international community to give the Taliban the time to learn.

“After 40 years of war, surely in six months you cannot govern with no experience,” he said.

Sameera is all too aware of the Taliban’s inexperience. What frustrates her the most is that there was already a system in place at the Afghanistan Ministry of Education, put in by the previous government. But, she said, when the Taliban took over, they fired all the qualified staff who could have helped them govern.

She added the Taliban’s credibility, which was not much to begin with, is all but gone.

“No one is trusting these people anymore,” she said.

(Bernama journalist Nina Muslim was in Afghanistan from Feb 23 to March 3, 2022, to do in-depth reporting of the situation on the ground six months after the departure of the US forces and the Taliban’s takeover of the government. She also accompanied Malaysian NGOs on their relief efforts coordinated by Global Peace Mission Malaysia.)

-- BERNAMA

Penulis

Nina Muslim

26 March 2022